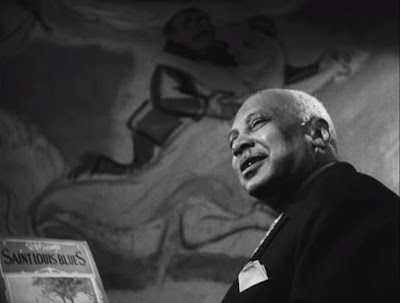

This film is considered a “watershed in the use of film to promote racial tolerance”, and Heisler had previously handled the subject with surprisingly fine results in his 1940 The Biscuit Eater. Hollywood showed little interest in the subject of race, apart from work by those communist writers such as Lester Cole (None Shall Escape) and John Howard Lawson (Sahara) who gave African Americans a voice as agents of democracy in the fight against fascism. However, The Negro Soldier was perhaps the only film in that vein written by an African American, Carlton Moss. Films about the black experience were either ‘churchy’ or ‘bluesy’ (a rare exception, King Vidor’s 1929 Hallelujah! was both). The Negro Soldier is churchy (even if it does include a fleeting shot of the father of the blues, W.C. Handy), adopting the form of a sermon, in which the history of African Americans’ involvement in the making of America is recounted to an entirely black audience. But when the familiar image of the church minister at the pulpit arrives, it delivers a twofold punch: it is Moss himself – and the book in his hands is Mein Kampf, from which he reads Hitler’s perspective on the black race. The church form finds new urgency, as the film’s writer merges roles with that of the minister. Heisler makes his point visually, to avoid preaching: at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the German and Japanese athletes fail and an African American wins; a black conductor leads a mixed orchestra through Beethoven’s 9th Symphony.

Combining footage from fiction films, recreations of real events and newsreels, Heisler and Moss’s take on racial tolerance was perhaps too much for the Army: they demanded that some scenes be cut, such as one in which a black officer commands the troops, and another in which a white nurse massages a black soldier. That didn’t stop African American soldiers and the black press from admiring the film as a step towards a dignified image of their people on screen. — Ehsan Khoshbakht

No comments:

Post a Comment