My Guardian obituary on the late, great Bahram Beyzaie can be read here.

Monday, 29 December 2025

Saturday, 27 December 2025

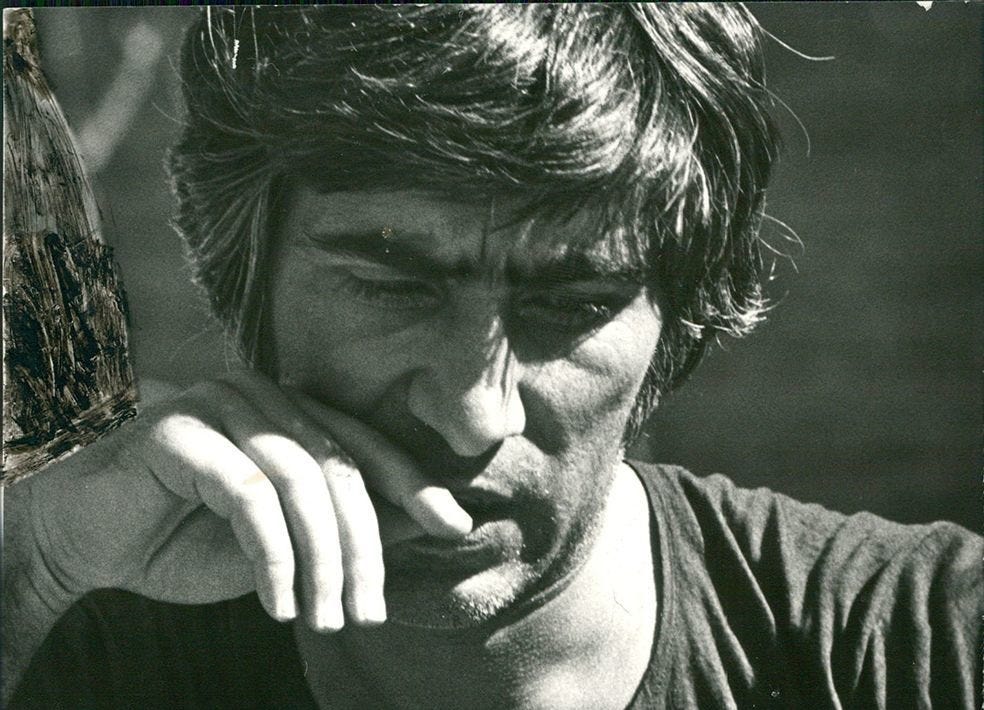

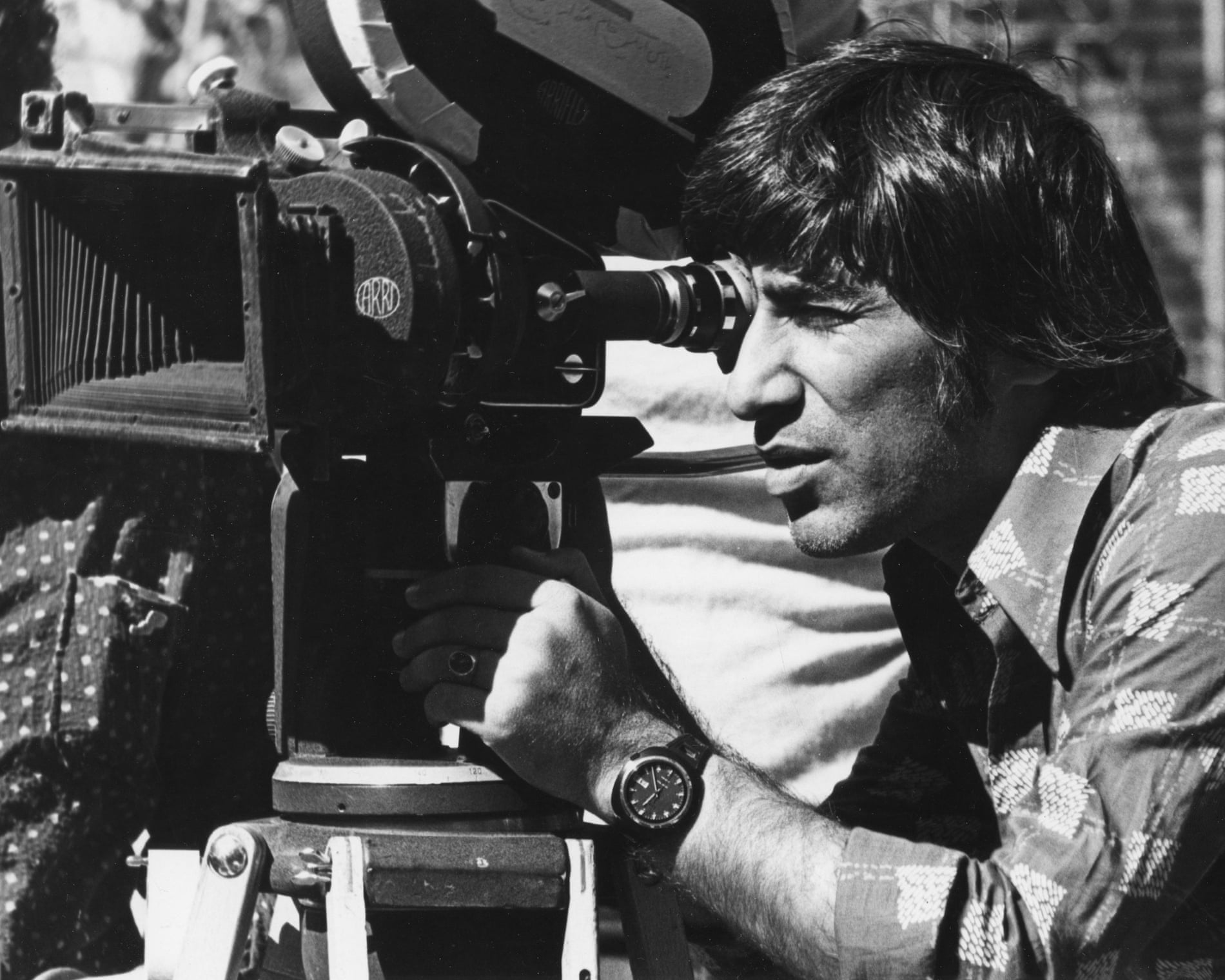

RIP Bahram Beyzaie (1938-2025)

|

| Bahram Beyzaie |

One of the guiding lights of Iranian modernist cinema since 1969, and an equally invaluable force in theater, literature, and history, Bahram Beyzaie passed away yesterday in California, where he had been based for the past 15 years.

For public screenings of his films, I have previously reviewed at least five of his works, which I share again here in memory of one of Iranian cinema’s most brilliant figures.

Ragbar [Downpour] (1972)

Safar [Journey] (1972)

Gharibeh va Meh [The Stranger and the Fog] (1974)

Kalagh [Crow aka Raven] (1977)

Cherike-ye Tara [The Ballad of Tara] (1979)

Ragbar [Downpour] (Bahram Beyzaie, 1972)

In this, one of the most accessible and beloved Iranian New Wave films, a young teacher is sent to a school in the impoverished south end of Tehran, where he falls in love with his student’s elder sister, and directs all his energy into helping the students put on a stage show. Moving, witty, and brilliantly directed in an energetic and unusual combination of neorealism and political symbolism, Bahram Beyzaie’s first feature was realized with a shoestring budget but managed with astounding success to blend its director’s roots in theater, literature, and film history with a story that, even to this day, resonates powerfully with Iranians. — EK

Monday, 22 December 2025

Ladies in Retirement (Charles Vidor, 1941)

Based on the Broadway play, Ladies in Retirement is one of Columbia Pictures’ very few Gothic films, and one of the finest of the genre in the 1940s. Ida Lupino plays a spinster housekeeper and live-in companion who brings her “crazy” sisters (Elsa Lanchester and Edith Barrett) to the secluded mansion, later joined by their shady nephew (Louis Hayward) whose main interest is in the wealth of the gullible lady of the house.

Sunday, 21 December 2025

Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave, Part II at the Barbican, London

|

| Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure |

Following the Barbican Centre’s sell-out programme Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave in February 2025, the second part will present an even richer array of rare cinematic gems, many of them never before seen in the UK.

Featuring numerous new restorations, this expanded foray into the classics of Iranian cinema that first brought worldwide admiration to the nation’s film culture will include the world premiere of the newly restored director’s-cut version of Ebrahim Golestan’s satirical film Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure. Starring Parviz Sayyad, Mary Apick, and Shahnaz Tehrani, this long-unseen version has been restored by Cineteca di Bologna in partnership with the Iran Heritage Foundation.

Saturday, 20 December 2025

Interview with Shadi Abdel Salam

Conducted by Tehran International Film Festival and published in their daily journal, November 28, 1974. Originally in Persian. Abdel Salam’s words are glamorous, barren, and true—like his film Al-Mummia. The translation is mine. — EK

Al-Mummia, your first feature film, made in 1969 and received great critical attention, has not yet been screened in Egypt. Can you explain this?

Shadi Abdel Salam: I don't really know why the film wasn't shown. Maybe the authorities are afraid that people won't understand it. Anyway, my job is to make a film, not to navigate the labyrinths of bureaucracy. Currently, there isn't even a copy of this film in Egypt to participate in festivals.

Sight & Sound | The best films of 2025

Monday, 1 December 2025

Athens Avant-Garde Film Festival | Restored section's introduction and notes

Introduction to and programme notes for the "restored and beautiful" section at the 14th Athens Avant-Garde Film Festival, December 2025. — EK

The films in this section, spanning six formative decades of cinema history, start and end in the Middle East, offering a sense of the resilience of its people. The canonical documentary masterpiece Grass (1925) follows three Americans traveling among the nomadic tribes of Iran, while Ghazl El-Banat (1985) adopts an insider’s point of view in which the great Arab filmmaker Jocelyne Saab gently removes the shrapnel from the wounded body of her hometown, Beirut.

If Ghazl El-Banat is its director’s finest work, then Craig’s Wife (1936) is the masterpiece of American director Dorothy Arzner. A tale of a toxic lady of the house, no melodrama has so precisely and exhilaratingly explored the intertwined themes of house, territory, and power.

Wednesday, 26 November 2025

My Sister Eileen (Alexander Hall, 1942)

Based on a play by Joseph A. Fields and Jerome Chodorov—which itself was adapted from a series of autobiographical short stories by Ruth McKenney—My Sister Eileen was later remade by Columbia in 1955 as a CinemaScope musical directed by Richard Quine. It follows the misadventures of two Ohio sisters in their search for love, fortune and an apartment to rent in New York. Rosalind Russell plays the older sister, determined to pursue a career in journalism, while also finding herself both chaperoning and competing with her younger sister Eileen (Janet Blair), whose dream of becoming an actress draws all the wrong people to their cramped basement apartment.

Tuesday, 25 November 2025

None Shall Escape (André De Toth, 1944)

Playing at Harvard Film Archive on December 8 and 14. — EK

A rare exposé of Nazi atrocities made while the crimes were still ongoing, None Shall Escape is boldly framed as a speculative post-war tribunal that revisits the actions of a German schoolteacher (Alexander Knox) turned Nazi and the horrors he inflicted on a Polish village. Impressed by André De Toth’s Hungarian films, Harry Cohn hired the director after his arrival in the US in 1940. Following a routine B-movie assignment, De Toth—who had personally witnessed and even filmed the Nazi occupation of Poland—was given None Shall Escape; its title echoing President Roosevelt’s pledge of postwar justice.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)