|

| Forugh Farrokhzad directing The House Is Black (1962) |

From the September issue of Sight & Sound:

1

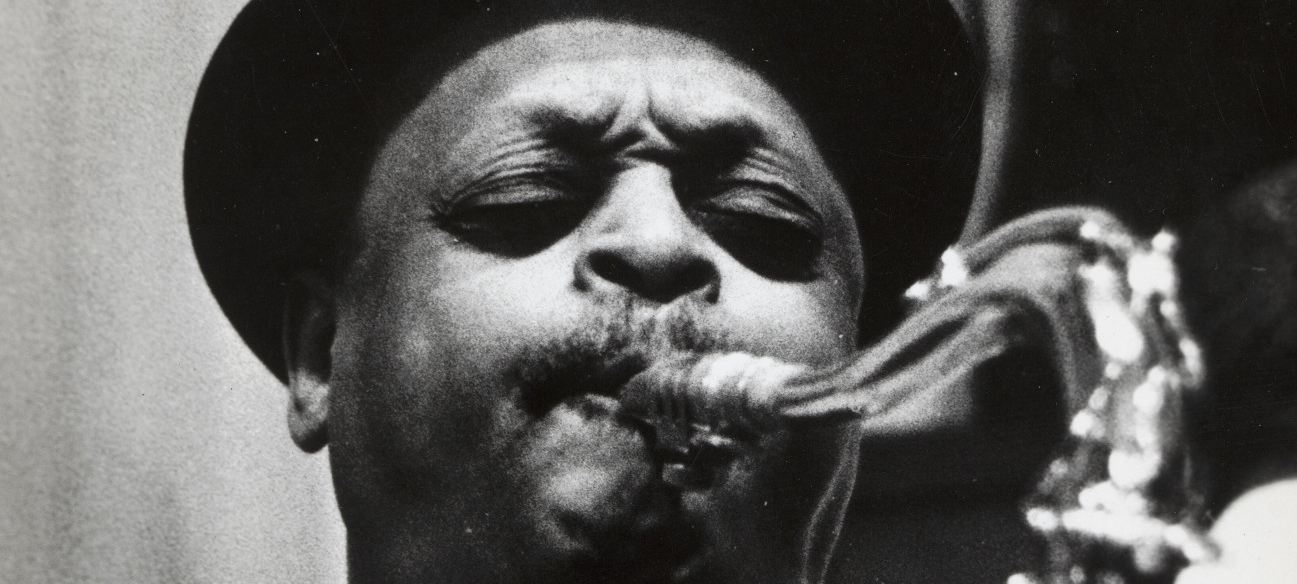

The Sound of Jazz (Jack Smight, 1957)

This is the greatest improvised documentary ever, and features a super-stellar line-up of 32 leading jazz musicians gathered at the CBS Studio in New York City in December 8, 1957. It was made in one hour and broadcast live on television. Cameramen were as into ad-libing as Thelonious Monk, and when Billie Holiday and Lester Young started to play Fine and Mellow everybody in the control room was crying.

2

Quince Tree

of the Sun (Victor Erice, 1992)

Documentary cinema as meditation. No film, fiction or documentary, has captured the meticulous, painfully stagnant process of artistic creation with such rich expansion of cinematic time and space.

3

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985)

There is a logical, aesthetic and moral relation between the scale of the tragedy and the length of the film, which leaves a lasting physiological and psychological impact on the viewer.

4

Histoire(s)

du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1988)

A multi-dimensional, free-form history of 20th century which proves all one needs is some ideas and an editing table, because the images are already out there.

5

The House Is Black (Forugh Farrokhzad, 1962)

The crowning achievement of Iranian documentary movement of the 60s and 70s, and singular in its hypnotic melancholy, its profound humanism and its poetic imagery.

6

Hôtel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie (Marcel Ophüls, 1988)

This film taught me the methodology of cinematic inquiry, as well as lessons in persistence and integrity. In every documentary Ophüls has ever directed, he proves that cinema is, above all, a machine of humanism, if one knows how to use it.

7

Robinson in Space (Patrick Keiller, 1997)

My traveling guide to Britain. Behind its cold, bureaucratic, un-poetic shots, lie a majestic world of complex emotions.

8

Lektionen in Finsternis (Werner Herzog, 1992)

I was born and raised during the Iran-Iraq war, and every bit of the horrendous landscape portrayed on this film is also carved in my memory. What Herzog with his hel(l)i-shots does is to dive into that collective memory shared by millions who were inside that hell.

9

P for Pelican (Parviz Kimiavi, 1972)

A haunting and stylized mediation on solitude, beauty and language through the story of a real-life protagonist, Agha Seyyed Ali Mirza, who’s been living in the ruins of the earthquake-shaken Tabas for forty years. A day arrives when he has to leave the ruins and face the great, strange, Lynch-like beauty: a pelican!

10

The Battle of Chile (Patricio Guzmán, 1976)

The film’s bleak transition from the hope and ardor of the first part to the harrowing shot-from-the-rooftop second section, tells not only of the history of Chile, but also of the process of toppling other democratic governments in 20th century (namely, Iran of 1953).

|

| Sound of Jazz (1957) |

Notes:

In order to narrow down the range of choices, I exclude documentaries if an experimental nature such as great city symphonies of the late silent era, as well as actor-less fiction films such as Soy Cuba.

There are many jewels of documentary cinema hidden in the vaults of TV stations. In that regard, Cinéastes de notre temps, a French produced-for-TV film-portrait of masters of cinema, of which only a few titles are available to the public, is the greatest film university one can attend, as well as a perfect example of a masterpiece produced by filmmakers whose names are not yet in the canon.

As a trained architect who has designed, written and filmed about architecture and cinema, I still feel there are many unexplored territories in this field, and that many great films are waiting to be made. However, it doesn’t mean overlooking what’s already been done, especially works of Thom Andersen, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Man Ray and Alexander Kluge.

Lastly, there are directors whose body of work has influenced me more than any single film. Georges Franju’s early work, Fredrick Wiseman and Chris Marker are among them. Kamran Shirdel’s clandestine documentation of the lives of unprivileged in pre-revolutionary Iran, in pa

rticular, stands out.

|

| P Like Pelikan (1972) |