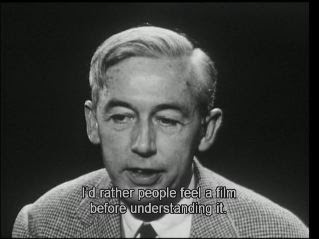

Segments from a Cahiers du cinéma interview with Fritz Lang in 1959. Interviewers are Jacques Rivette and Jean Domarchi.

- Do you prefer your American films or the German films?

That's very difficult. It isn't a question for me of an excuse. I don't know what I should say. It isn't for me to say, you know. One believes that the film one is making will naturally be the best. We are simply men, not gods. Even if you don't believe it will be less important, even the mise-en-scene, than this or that earlier film, you still try to make your best work.

- Of course. Also, within the different periods, German or American, are there certain films to which you feel more attached?

Yes, naturally. Listen. When I make blockbusters, I am interested in people's emotions, in the audience's reactions. That's what happened in Germany with M. In an adventure film or a crime film like Dr. Mabuse or Spione, there is only pure sensation; the development of character doesn't exist. But, in M I began something quite new for me, something that I followed in Fury. M and Fury are, I believe, the films I prefer. There are others as well, which I made in America, Scarlet Street, The Woman in the Window, While the City Sleeps. These are all films based on a social critique. Naturally I prefer that, because I believe that critique is something fundamental for a director.

- What exactly do you mean by social critique, that of the system or that of civilization?

One can't really differentiate. It is the critique of our "environment," of our laws or our conventions. I will admit to a project. I must make a film where I put all my heart. It is a film which shows modern man as he is: he has forgotten the true meaning of life, he works only for things, for money, not to enrich his soul, but to gain material advantages. And because he has forgotten the meaning of life, he is already dead. He is afraid of love, he simply wants to go to bed, make love, but he doesn't want any responsibilities. He only wants to satisfy his desire. I think it is important to make this film now. While the City Sleeps shows the hard competition of four men inside a newspaper office at the beginning. My personality refuses the personal satisfaction of being a man. Because each of us, these days, is looking for position, power, money, but never anything inside. You see, it is very difficult to say, “I like this or that.” When one begins a film, maybe one doesn't even know exactly what one is doing. There are always people to explain what I want to do, and I say to them, “You know more than I.” When I undertake a work, I try to translate emotion.

- In fact, is what you are critiquing in your films a sort of alienation in the German sense of the word “Entfremdung” (Estrangement)?

No, it is the fight of the individual against circumstances, the eternal problem of the ancient Greeks, the fight against the gods, the fight of Prometheus. It's the same today, we fight against laws, we fight against imperatives which don't seem just or good for our times. Perhaps it won't be necessary thirty or fifty years from now, but it is now. We are always fighting.

- Is that the case for all your films, for Rancho Notorious, for While the City Sleeps?

Yes, for all my films.

- Even for Die Nibelungen?

Exactly, but I think that film has become too big to go into its minutiae.

- All the same, in Metropolis, that subject is already very clearly indicated.

I am very severe about my work. One cannot say now that the heart is the mediator between the hand and the brain, because it is a question of economics. That's why I don't like Metropolis. It's false, the conclusion is false, I don't accept that I made that film.

- As for the end of Fury, you don't reject it?

No the end of Fury is an individual ending, not a general conclusion. One cannot give recipes for living. It is impossible.

- Finally, the lesson of your films will be that each man must find his own solution.

I think so. Man can revolt against things that are bad, that are false. One must revolt when one is "trapped" by circumstances, by conventions. But I don't believe murder is a solution. Crimes of passion do not solve anything. I love a woman, she betrays me, I kill her. What is left? I lost her love and she is dead. If I kill her lover, she will hate me and I will still lose her love. Killing is never a solution.

- What then for you is a solution? For example, for the heroes in While the City Sleeps, what is the solution for them, because the conclusion of the film appears to be very pessimistic, even full of bitterness.

I don't believe life is very easy. But my conclusion isn't pessimistic. We see the fight between four men over social position, one for money, another for power, the third, I don't remember, the last because he liked to do that. But the man who wins against the others is the one with an ideal. Which means that, if you always do what you must do without detesting it, if you never need to spit in the mirror in the morning, you get what you want. Where is the pessimism in that?

- We have the impression that the sympathetic hero is not as sympathetic as that.

That's something else, that's something else.

- No, we would like to say that the tone of the film. . .

The tone of this film is perhaps a glimpse of a film that I want to undertake now, a critique of our contemporary life, where no one lives one's personal life. We are always under work-related obligations that are very important. After all, money is important. Often critics ask me why I made such and such a film. The truth is that I need money. Somerset Maugham wrote that even artists have the right to make a living.

- In the meantime, are there films which you made for money and in which you had no interest?

- What brought you to make a Western like Rancho Notorious?

First, I wanted to show that there could be a woman who could lead a gang, and a man who could be a celebrated hold-up man, but because he is too old, and because he doesn't draw his gun as quickly, he was no longer a hero. Along comes a young man who shoots more quickly than the older man. The eternal story. Then there was an interesting technical element: to introduce a song as a dramatic element. With six or eight lines of the song, I arrived more quickly at the conclusion, and I avoided showing certain things which would be more boring for audiences, and which weren't very important for the film.

- At that time, did you see, and do you now watch many Westerns?

Yes. I like Westerns. They have an ethic that is very simple and very necessary. It is an ethic which one doesn't see now because critics are too sophisticated. They want to ignore that it is necessary to really love a woman and to fight for her. When I was making Der Tiger von Eschnapur, I argued with my screenwriter because I wanted the Maharaja to say, “If you give me your word of honor, I will let you free in my palace,” and the screenwriter answered, “Listen, everyone will laugh. What is a word of honor worth today?” Admit that that is very sad. There are today no contracts which I cannot break or which my partner cannot break. What is one hundred pages worth? If he refuses to give me the money, I am obliged to go to court and spend five years. Same for me. If I refuse to honor my contract, no one can force me to. That's idiotic. Whereas, if I give my word of honor, that binds me more. These are fundamental ideas that should be repeated to young people because each year there is a new generation. In Berlin, I saw a German anti-war film. The reviews were terrible, under the pretext that the film did nothing original, that it brought out old themes. But what new things can we say against war? The important thing is that one repeats these things again and again and again.

- Do you consider cinema a medium of persuasion and education?

For me, cinema is a vice. I love it infinitely. I've often written that it is the art form of our century. And it should be critical.

- What circumstances led you to make Human Desire, and for what reasons did you change the ending and what led up to it?

Renoir's film is better. First, I had a contract. If I had refused, they would have said, “Perfect, but if we have another film for you, because you've made money on this one, you won't make any more.” That could last one or two years. So I am inclined. Then the producer says to me, “That's understood, we like the Renoir film very much, but we can't make 'perverse sex.' We need a young, clean-cut American.” In fact, he was right because censorship would be opposed to someone like Jean Gabin. You couldn't imagine the difficulties that we had in finding a rail line that would authorize takes under the pretext that we would show a murder. They said to me, “On our line, a murder, but that's impossible.” And they were right, absolutely right. Could you believe that the authorities for the Santa Fe Railroad would be very happy to see a film with a murder on one of their trains? Who could make a film on the human beast if he doesn't follow the book? My film isn't La Bete Humaine. It was called, in English, Human Desire. It was inspired by a book, a film. I wonder why you gave it a good review in your Cahiers du Cinema.

- Formally, your film is very good.

Thanks very much, you are very kind, but it wasn't La Bete Humaine.

- To return to your ideas on the Western, you have frequently addressed an objection from numerous critics, one that we don't share, that reproaches you for your taste for melodrama. Do you not like this so-called melodrama, as much in your Westerns as in your Policiers, as in your films with romantic triangles, in the measure that they permit stronger situations, where people, men, are more revealed?

I don't care that it's a melodrama, I don't know. The truth is what I often see in my observations about murderers, I am frequently in places where a crime has been committed. I don't think that what I've seen is melodrama. As well, it's not up to me to critique critics. I make a film, it's a child which I put out to the world. Everyone has the right to critique it. That's all. Permit me the only vanity that makes me happy: public approbation. I don't work for the critics but for audiences whom I hope are young. I don't work for people of my age because they should already be dead, me too. I don't want to come to Paris. This cocktail, these few words in front of the public at the Cinematheque, I told Lotte Eisner, this reminds me of a monument for an unhappy man who isn't yet dead. She is right. A young public has really responded. I was very moved, very moved, because that proved that I hadn't worked for nothing.

- You told us earlier that the director's goal was to critique. Couldn't that be the definition of mise-en-scene?

All art, I believe, should critique something. It isn't enough to say it's good, it's enticing, it's marvelous. In any case, what can one say of a woman who is good? She's a good mother, a good wife. But what can one recount about a bad woman? One can speak for hours about her, she is interesting [Laughs]. Yes or no? You say about one that she is good, but the other. ... The question is, “Why is she bad?”, “Is she really bad?”, “What right has she?”, “What were the circumstances?”, “Weren't men responsible?” One could talk all night. And we could talk all night with her. [Laughs] I saw, here in Paris, an English film called Room at the Top. There were two women, one very frank, the other very bad. Simone Signoret was the most interesting, not because she was the better actress, but because her sentiments were the more passionate.

- In what way were you influenced by or have you worked against the Expressionist current?

I was very influenced by it. One cannot live through a period without taking some of it in.

- Die Nibelungen seems expressionist in the best sense of the term, whereas Caligari seems expressionist in the very worst sense.

You are wrong. Because Caligari is an interesting attempt, it was the first attempt. When Wiene tried again with Genuine, that didn't work. The cinema is a living art. It is necessary to take all that is new, not without examination, but all that is good for you, all that enriches you.

- What seems to you to be good in the Expressionist movement, what did you use in your films?

That is difficult to tell you; that which I take is my emotion. I try to create something. In this type of interview, one asks me to explain what I would like to have done. One day, in America, some admirers showed me what I thought when I made M. I said to them, “That's very interesting, but that's the first time I realized it.” I can't really answer you, these are emotions. When young directors come to ask me, “Could you give us rules for directing,” I tell them “There are no rules.” Today I see that something is good, I should go in that direction, tomorrow I say it isn't right, I should take a different direction. I used the train and now I use a plane, but it is impossible to pretend that the train is bad. I can't say what I found in Expressionism. I used it, I tried to absorb it.

- Certain of your colleagues like to develop theories of art, in particular Eisenstein, who wrote a number of theoretical articles. Aren't you also tempted to develop theoretical considerations about your work in the same sense as Eisenstein about his own work, and then generalize those theories to all cinema?

I believe that when one has a theory about something, one is already dead. I don't have time to think about theories. One should create emotions, not create under rules. To work with rules is to work with one's experience, is to fall into routine. I know a man named Mr. Kracauer who wrote a book called From Caligari to Hitler. His theory is absolutely false. He used all his arguments to prove a false theory. I therefore feel forced to dissuade today's youth from believing in a book that is full of idiocies. I told him. He was very angry. [Laughs] You know I have a language, I simply use it and I can prove anything. But it isn't necessary for my truth. A theory is nothing for an artist, it serves only for people who are already dead.

- Did you know Murnau in Germany?

Yes, but not very well. He left very early for America, and was already dead when I arrived there. He had made his excellent works. He was a very interesting personality. He made Nosferatu, very, very good. Tabu, and even a Faust where we find very, very passionate things.

- What do you think of Nicholas Ray?

I've seen two or three of Ray's films that I like very much. Rebel Without a Cause is a very good film.

- His first film, They Live by Night, was inspired by your films.

I accept that. Listen, I've stolen things from other directors, and I am very content and very proud if someone steals something from me. What does that mean, steal? One takes an idea that one admires and one tries to make it one’s own.