From the Saturday Evening Post, December 29, 1945, vol. 218, no. 26

PICTURES FOR PEANUTS

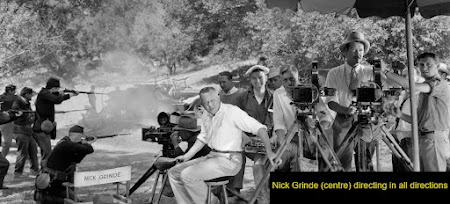

By NICK GRINDE

Over on Stage 6 a million-dollar picture is starting this morning. The call was for nine little well-placed optimism you could say that the epic is beginning to show promise of getting under way. A lot of departments with a whale of a lot of mighty fine technical abilities have been working for weeks toward this very day. Propmen, grips, gaffers, electricians, boom men, recorders, mixers, cameramen, assistant cameramen, a script clerk overflowing her rose-colored slacks, a company clerk, an assistant director, his assistant and his assistant are functioning with the occupational movements that will find each one ready when the moment-finally comes to record the suspensive scene where Nancy says, ‘I am tired of wearing other people’s clothes. From now on I will wear my own or nothing!”

This confused efficiency, laced, of course, with a fine sense of self-preservation, is going on, all unnoticed, around, above and in between the associate producer and the director, who already are trying to see who can stay calm the longer. The pattern is familiar to everyone. Too much has been written about the habitat of the colossal picture for anyone to have escaped a willing or unwilling education on the subject.

But over on Stage 3 in this same studio another picture was scheduled to start this morning: at eight-thirty. It’s ten-thirty over there, too, and they have exactly two hours’ work under their belts. There are no press agents or fan-magazine writers hovering around. No newspaper columnists are harvesting their succulent crop. You’d think it said “Contagious” on the door instead of “Quiet, Please! Shooting!”

The difference is that this is just another little picture. A B picture, if you please. B standing for Bread and Butter, or Buttons, or Bottom Budget. And standing for nearly anything else anyone wants to throw at it. But it’s a robust little mongrel and doesn’t mind the slurs, because it was weaned on them. If the trade papers give a B the nod at all, they usually sum up their comments by saying it will be good for Duals and Nabes, which is why you'll find them on a double bill in the neighborhood theaters.

A B picture isn’t a big picture that just didn’t grow up; it’s exactly what it started out to be. It’s the twenty-two-dollar suit of the clothing business, it’s the hamburger of the butcher shops, it’s a seat in the bleachers. And there’s a big market for all of them.

Only by perpetual corner cutting can these often quite presentable cheaper pictures be made to show the profit that is so very agreeable to the studios which invested their money in them.

Like the less expensive suit of clothes, the cloth from which they are fabricated is not all wool, the buttonholes are machine made, and the buttons themselves are more or less synthetic. But when you are all through, you have a suit or a picture which goes right out into the market with its big brothers and gives pretty good service at that. The trick is to judge them in their class and not by A standards.

In the finer pictures, results are all that are aimed at, let the costs fall where they may. The best possible actors are hired to articulate the finest lines the top writers can conjure up. And the best directors mount the stories in convincing and appropriate settings. Of course, occasionally somebody’s aim is a little off, but that’s beside the point.

In making a program picture, all this is different. Cheaper raw materials are used and a more thrifty approach is indicated. No expensive best seller or Broadway play is bought. That’s out; it’s not even thought about. The whole picture will be made for much less than the cost of such a property. The story used will be an original submitted by one of the freelance writers who knows just what and whom he is slanting it for. Or it may be a magazine story from one of the pulps or a fifteen-minute radio program purchased for its basic idea or twist. These properties are then blown up into script form and length by a writer who either works at the studio already or is brought in for the job. If he gets six weeks’ work out of it, he’s lucky. If he takes much more, he had better buy bonds with the money, be- cause he won’t be back very soon.

There are all kinds of ways of writing a story besides good and poor. It can be written up or written down. It can be costly to produce or slanted on the frugal side. If the cast of characters can’t be held down in numbers, it’s the wrong story for limited money. And if they can’t be kept out of busy places like night clubs, railroad depots and football games, look out for the budget.

|

Beating a Cover Charge

Basic emotions can happen in a quiet place as well as at the Stork Club. If John and Peggy are cast in modest circumstances, they can wear their own wardrobe, and a set suitable for their home can be found already standing somewhere in the studio. It’s easy when you get the knack of it. Then, instead of taking her to a bustling restaurant for lunch and having some costly busybodies come by and tell them about the murder, they can be discovered coming out of the restaurant and shutting the door on all that expense. A reasonably priced newsboy can sell them a newspaper, so they can read all about the homicide. John’s reaction to the bumping-off of his best friend will be of the same fine stuff out here on the sidewalk as it would have been over a crepe suzette.

John, being who he is, naturally has to catch up with the rat who did it before the police do. There’s a matter of a good name and a hunk of money involved. But does John’s search take him to crowded bars, well-filled hotel lobbies, busy downtown streets, bus tops and other gregarious rendez-vous? Not by two budgets. He interviews a rooming-house proprietor who lives in a little standing set at the edge of town, and who is home alone at the moment. Then he talks to a milkman in front of a brownstone set on the old New York street. The milk wagon really isn’t expensive when you consider that it hides a big hole in the front of the house where some gangsters dynamited their way out in the second episode of a serial last week.

When John finally gets into the chase at the end of the picture, does he search the affluent Union League club, or a museum, or the zoo? You guessed it, cousin, the scene is shot in an alley with three cops and some dandy shadows. And if it’s done properly, it can be plenty thrilling, even if it is mounted in cut-rate atmosphere.

There are comparatively inexpensive ways of larding a story with a semblance of size and scope just waiting for the resourceful producer. One such fellow is a whiz at using stock shots from newsreels or any other fertile source. Whenever a building is blown up, or a bridge blows down, or a forest burns, or a strike riot breaks out, the chances are that someone is right there making a movie of it. If the stuff is good, this producer will buy a batch, paying for it by the foot, and have a whole story written around it or at least an important sequence. If you have a real forest fire to cut to, you can do wonders with a little cabin, a few trees, a wind machine, sun- dry lycopodium torches, and a batch of smoke pots. And you will have avoided the spending of up to $100,000 or more. If you’re lucky and things work out right, you can make quite a dent in your picture right here, and you'll probably come out with a climax that will bring a pleasant look from the front office. If you’re real careful and have the wind blowing from the same direction as the wind blew in the original film and watch your smoke density, the real and the staged films will cut together like well-hung wallpaper.

Other stock footages that have inspired important sequences are those of train wrecks, rodeos, the rescue of downed aviators, shipwrecks, kidnap manhunts, and even baby shows. You may not end up with the story you started out to make, but look at the wallop your detour gave you. And you van always salvage the abandoned sequences in another lot.

One studio struck oil by buying foreign films that had great scenic values and plenty of long shots. These films were bought outright, negative and all. Then a new story was written around these long shots and American actors hired to play the few reels needed to go with the salvaged scenery. The only demand on the refurbished plot was that the writers had to dream up excuses for their characters to go through the same scenic exteriors in the same groupings and dressed exactly the same as in the original. In that way, all the picturesque entrances and exits could be retained. Shooting the outdoor close-ups and the interior sets for the new version was a routine matter, quickly done. But the total result was very dressy indeed, thanks to the Swiss Alps shot by somebody else and bought for peanuts.

Borrowed Thrills

Another sleight-of-hand trick that’s used every day in the B-hives is the so-called montage. That’s a series of quick cuts of film borrowed from earlier pictures. It’s the Lend-Lease of the studios, Whatever the subject, there is always film available from some other fellow’s picture that will add otherwise prohibitive flavor to a sequence.

Say it’s a gangster film. Tony and his mob have been terrorizing the city for months. You can’t shoot a first-class crime wave on short dough, so you borrow or buy about twenty pieces of thrilling moments from twenty forgotten pictures. A fleeing limousine skids into a streetcar, a pedestrian is socked over the head in an alley, a newspaper office is wrecked by hoodlums, a bomb is thrown into a dry-cleaning truck, a woman screams, a couple of mugs are slapping a little merchant into seeing things their way. And so on until we end up on a really big explosion. All this, garnished with sound effects and crescendo orchestration, dissolves through to three serious-looking actors in a standing set. One of the men says, "This city has got to be cleaned up. Tony and his mob have got to go." And this is Scene I in the script which will be shot on Stage 3.

Montages can take care of World War I or II, a cross-country journey, a college education, a rise from poverty to riches or anything else too expensive in time and money to photograph. Often the determined face of the leading man is superimposed over this potpourri to remind you it is he who is having all these experiences. Of course, he’ll never know how he suffered until he sees the preview.

One producer fell in love with a reel of train wheels. Somebody shot too much of a speeding train one day. Probably the wind on the handcar which was following the engine’s underpinning with the camera was so strong that the cameraman couldn’t hear the command to cut. Or something Anyway, here was all that lovely footage of train wheels going somewhere.

The producer never really rested right until he found a story where the characters pursued one an other from city to city. Every time Joe thought he was being shadowed he got that don’t-fence-me-in look on his face and they dissolved to a hunk of money-saving train wheels. Then, of course, the detective, who either had to get a clue or end the story right there, got his portion of the wheels, and we knew that he was right after Joe again. So they chased from city to city, using up more and more train wheels, until the picture ended up in a draw between moving drama and galloping wheels

Stock stuff is not the only thing that is borrowed. Plots are hijacked in broad daylight. The fellows who make the dehydrated films are the most consistent disciples of the biggies. Gold isn’t the only thing that’s where you find it. If the brand on a cow can be changed with a hot iron, the earmarks of a situation can be camouflaged with a typewriter.

One of the most comforting things about plot lifting is that there are no new plots, and the fellows you raid have no doubt had their own little forays into the published works of even earlier shanghaies Plagiarism is a nasty word, but only for amateurs.

Several years ago, a major studio made an star picture with a costly scenario wherein a character who was a whaler by trade and went on long trips to sea, as whalers do, was double-crossed during his absences by a landlubber. Things went like this for a while, until one day the whaler had his leg bitten off by a shark who got into the picture somehow. Well, the wife wasn’t so much of a heel that she could let him down in his hour of need. So she nursed him, but during his convalescence he could see which way the prevailing wind was blowing. All of which made for quite a neat triangle Several years later, a producer at the same studio needed a story, but had very little money allowed him with which to get it. He remembered the whale picture, and also realized that it was all paid for. So he told one of his writers how to retread the plot. At the preview of this reclaimed yarn, a lion tamer was being double-crossed by a tightrope walker every time he went in the cage for his act. He suspected it a little, which made him careless, and the lion bit his leg off. Well, the wife wasn’t so much of a heel that she could let him down in his hour of need. So she nursed.... See how it’s done?

A beautiful set built for one of the more affluent productions has a pull like gravity to the fellow with the short moneybags. He haunts the side lines, drooling while the aristocrats shoot their leisurely schedule. Then he collars the big boss for permission to get his cast in there for just a few hours. The answer is no, of course. It always is at first.

He explains that the way he will shoot it no one will recognize it for the same set. He'll have his director pick new angles and re-dress the foreground. His picture is all action anyway, so it will feel like a different place entirely and it won't conflict a bit with the A picture; he'll underwrite that. And what a production lift it will give his otherwise barren little efforts. It will save it! He will even agree to shoot at night while the rightful occupants sleep. He’ll be in and out, and they’ll never know it.

As soon as he has gained his point, he calls the assistant director from his picture and instructs him to change the schedule to accommodate the plucking of this nocturnal plum. Then he drops in on his writers, who are now busy dreaming up a new script and who have already completely forgotten the one now shooting. He tells them to drop everything for an hour or two and whip up a night’s work in this set which will involve the principals and maybe up to ten or twelve extras, but no more. They point out that there is no conceivable way in which the characters of this yarn could find themselves in such a lavish set. The producer asks them who is paying their salaries, and would they just go down and take a look at the set, and hurry and write something and not be so touchy. There are at least a thousand reasons why the characters could find themselves in that set. All he asks them to think of is one— but by tomorrow night.

Of course, eventually the results of all this nomadic scheming are dumped into the busy lap of the director. It is he who is expected to manipulate these assorted ingredients into a presentable theatrical offering in what, with practically no understatement, might be called no time at all. The B director has to know more tricks than Harry Houdini did, and he has to pull them out of his hat right now-—not after lunch. He has to know a lot about making pictures and be able to toss that knowledge at a situation and hope that some of it will stick. He doesn’t have time to do any one thing quite as well as he would like to, because he can’t stop and do just that one thing. He is, for the moment, a juggler and must keep his eye on all the Indian clubs.

The scene to be shot is on the process stage. That, as you probably know, is where they put scenery from some- where else behind you and make you look as though you’d been there—a handy gadget if there ever was one. The set in front of the process screen is a Pullman drawing room. Outside of the train windows will appear, on command, the retreating countryside of Ohio— Can No. 76, Train Backgrounds; Right to Left; Please Return to Vault. In the scene will be the leading man and the leading lady and the Pullman porter, who is to bring them a telegram. It’s a short scene and won’t take long to shoot. Already the assistant from another company is sticking his nose in to see if shooting is progressing, as his company is scheduled to use this same process background screen in an hour from now. Only when his company arrives it will be Times Square which blossoms behind his heavies and the comic—Can No. 31, New York Streets; Daytime; Stationary; Please Return to Vault.

Assistant No. 1 tells Assistant No. 2 that everything will be on schedule somehow. It always is. The only slight drawback is the fact that the colored actor who is to play the part of the Pullman porter is conspicuously not there yet. Seems he has been contacted, though, and is even now arranging with a friend of his to pick him up where his car broke down and hurry him to the waiting train fragment. While the assistants are still talking, the director, long since indoctrinated to abhor a time vacuum, is having the leading man’s right hand blackened. Then, with the porter’s white coat on, it will be his hand that is photographed knocking on the drawing-room door. In the hand will be the telegram, and the shot will tell us visually that a porter has a telegram for the occupants of Room B. The shot will be even more effective than seeing the porter approach the door in a long shot as it was written, and, of course, it keeps the company working, which is what those precious fleeting moments were made for in the first place.

When this shot is finished the leading man will resume his original identity, and if the overdue Thespian is still not there, he will be photographed in his individual close-up receiving the telegram from the supposedly offscreen porter, and will answer his unspoken questions. By that time the missing actor will surely have arrived and the necessary three-shot of the group will be made, and it will all come out just as though it had been planned to be shot backward in the first place, whereas the only thing that had been planned for sure was to shoot, period. One director returned from a three-day location trip with the full confidence that a New York penthouse would be awaiting his directorial efforts. His script called for a refined high-society argument, followed by the blackmailer’s accidental crash through the penthouse window to the street far below. All of which led quite logically to a big courtroom scene which was to be the high spot of the picture.

It had been agreed to spread a bit and to spend a respectable part of the construction money on this particular set and really make something nice out of it. But in the director’s absence it seems that, just as work was about to start on the building of the penthouse set, the producer stumbled on a very charming garden pergola and a bright idea at the same time. The structure was set amid potted foliage and real grass mats, and had been used for an idyllic love scene in a recent Viennese picture. Why couldn’t the accident happen in the arbor of a pseudo-Long Island estate instead of on the roof top of a downtown building? A trifling detail, but a thrifty one. The switch was ordered immediately.

When the director heard about what they had done to him behind his back, he went into a condensed tantrum. By training and instinct he knew he had to hit his fury fast. He knew he was entitled to anger, wrath and indignation, and he also knew that if he took too long about it, he’d have a hard time getting back on schedule. So he pulled out all his emotional stops and inquired why, while they were at it, they hadn’t switched him to an igloo or a tepee. How, he demanded, could you plunge a man down to his death from the French window of a garden bower?

So, a couple of minutes later, when he started work, a gun was slipped into the struggle, and when the actors had choked all the dialogue out of each other, the darn thing went off, and everyone except the victim, who was now comfortably off the pay roll, turned up in the courtroom as per plan.

Another corner-chopping expedient is premised on the different rates of pay for bit actors, depending on whether or not they speak. A bellboy, for instance, who is not playing a part, but who is just in for the day to take someone’s bags to the elevator, will get $16.50 if he remains silent. But this is boosted to $25.00 if he articulates so much as a "Yes, sir" or "Thank you, sir." Nine times out of ten it’s awkward to keep him silent, but that’s how close these budgets are pruned. The actor says, “Take my bags to my room. I’ll go up later.” The bellboy nods silently and exits. Eight-fifty saved. Or the lady asks where the phone booths are. The bellboy points mutely, and the lady says, “Oh, thank you,” and the bellboy wishes he could have said it. It makes the hotel help look mighty surly, to say the least, but the silent bellboy is here to stay.

One director, who shall be nameless, but whom we'll call Nick, was given a $16.50-bit man who had so much to pantomime that he and everyone else ran out of ideas for suitable gestures. Nods, points, shrugs, smiles and scowls were all tossed to the camera, but there was still more plot and still the order to keep him frugally inaudible. So, like always, something had to be done. He was finally played as a character with laryngitis, and wrote his answers on slips of paper, which were then photographed and cut into the film. The part came out as a nice thrifty novelty.

So by shaving the corners of already clipped corners, by shooting backward and sideways to make budgets and salaries come out even, by re-dressing and doubling the same set three or four times, by shooting only the absolutely necessary footage, by concentrating on speed and novelty and plot pattern rather than on time-consuming characterizations and penetrating emotional studies, you can make a picture that may never get the Academy award, but will, however, have a healthy career and earn money.

Not all A pictures are good, any more than all B pictures are poor. You can get ptomaine at the classiest hotel and you can get a good steak in a dog wagon. Both kinds of pictures can learn something from the other. Today, with continuing manpower and raw-material shortages, it wouldn’t be a bad idea at all if the super-supers would funnel a bigger percentage of their efforts onto the screen and not on extracurricular waste motions.

By the same token, the quickies, which have brought the efficiency of getting their money’s worth down to a microscopic point, could improve their standing in the community if they would apply the same efficient diligence to seeing that their scenario material was a bit more honest. Fast cutting may hide a weak point in the script, but there is a ceiling on fast cutting. Unlike the V-2 bomb, it mustn’t go faster than sound—you guess why. So the best thing to do is to tighten up the story points with the same sure hand that whittles the budgets.

A bookkeeper hopped up on a stool in the studio lunchroom next to a director a couple of days after he had finished making a fast detective yarn.

The double-entry fellow said, ‘‘Say, your picture came out swell.”

The director, being human, rumors to the contrary, was delighted, and said, “Oh, have you seen it? The cutter told me it wouldn’t be ready till tomorrow.”

The answer was, “ No, I haven’t seen it. 1 mean you brought it in a day under schedule and nicely under the budget. Boy, you did a fine job!” Unfortunately, none of this praise comes under the heading of entertainment. When the picture gets to the theaters, its penny-pinching undergarments had best be covered by lace of amusement, or some rude patron of the drama will say, “Your slip is showing.”

THE END

No comments:

Post a Comment