|

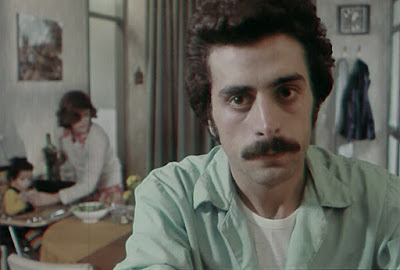

| Youssef Chahine |

One of the six* Youssef Chahine films which will be screened at Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019 is one of its director's epic works from the 1960s and his first film conceived as a co-production between Egypt and the Soviet Union. I haven't mentioned the title of the film yet as it's exactly the reason I'm posting the translation of this interview with Chahine: the confusion about the title of the film.

The film in question is about

Aswan Dam which was one of President

Gamal Abdel Nasser's most ambitious projects. It was built with the help of Russians after Nasser was turned down by Americans. Chahine was assigned to make a film about it with a cast from both Egypt and Russia and scenes shot around the Nile, as well as in Moscow and Leningrad.

However, the film was banned upon completion and Chahine was asked to do another film on the same subject. The title of the second film which he directed but didn't like was

Al-Nas va Al-Nil (People and the Nile, 1972). This film was distributed in Egypt and had some scenes in common with the "director's cut."

For years, that was the only version available until the original film was discovered in and restored by Cinémathèque Française. Chahine started calling his revived film

Al-Nil va al-Hayat (Life and the Nile).

|

| Poster for Al-Nas va al-Nil (originally shown in 70mm) |

In Bologna, we will be screening the latter version that Chahine liked and approved on June 26, 11AM, Cine Jolly. However, note that the Arabic title of the film in the opening sequence is still

Al-Nas va Al-Nil (People and the Nile) even if it is actually

Al-Nil va al-Hayat! At this point, I still don't know why.

Back to the troubled history of making this Nile project, Chahine explained the genesis of the film and the problems he had in an interview with newspaper Al Hayat. I have used Google translator and my basic knowledge of Arabic to make this text available to you, as I believe the information given here is important in avoiding the confusion regarding the title of the film.