|

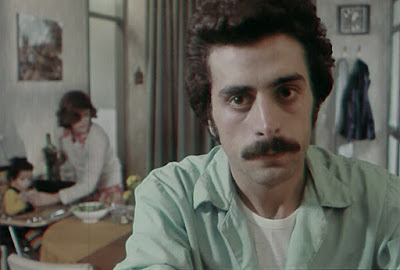

| Abbas Kiarostami in Homework |

An essay written for the Criterion release of Abbas Kiarostami’s Early Shorts and Features Blu-ray set. – EK

Abbas Kiarostami’s cinema is one of journeys. His films travel meandering routes, and his own path to international fame and recognition as one of cinema’s greatest directors was likewise mysteriously understated and subtle, almost imperceptible: a journey with marvelous detours.

Across a career marked by restlessness, which saw him making films not only in Iran but in France, Uganda, Italy, and Japan, the tireless filmmaker repeatedly reset his rules, moved from analog to digital, and transitioned from narrative film to video installations. Even as he came to be celebrated worldwide for beloved films such as Close-up (1990) and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), whenever the conventional definitions of cinema became too limiting for him, he pursued creativity elsewhere. He rewrote classic Persian poems and published them in books of sparse, haikulike verses that resemble images, and he took strikingly abstract photographs of solitary trees in snow that feel like distilled poetry. His life was proof that a filmmaker could create singular images even without a movie camera.