From the Saturday Evening Post, December 29, 1945, vol. 218, no. 26

PICTURES FOR PEANUTS

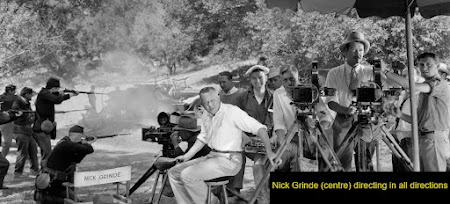

By NICK GRINDE

Over on Stage 6 a million-dollar picture is starting this morning. The call was for nine little well-placed optimism you could say that the epic is beginning to show promise of getting under way. A lot of departments with a whale of a lot of mighty fine technical abilities have been working for weeks toward this very day. Propmen, grips, gaffers, electricians, boom men, recorders, mixers, cameramen, assistant cameramen, a script clerk overflowing her rose-colored slacks, a company clerk, an assistant director, his assistant and his assistant are functioning with the occupational movements that will find each one ready when the moment-finally comes to record the suspensive scene where Nancy says, ‘I am tired of wearing other people’s clothes. From now on I will wear my own or nothing!”

This confused efficiency, laced, of course, with a fine sense of self-preservation, is going on, all unnoticed, around, above and in between the associate producer and the director, who already are trying to see who can stay calm the longer. The pattern is familiar to everyone. Too much has been written about the habitat of the colossal picture for anyone to have escaped a willing or unwilling education on the subject.

But over on Stage 3 in this same studio another picture was scheduled to start this morning: at eight-thirty. It’s ten-thirty over there, too, and they have exactly two hours’ work under their belts. There are no press agents or fan-magazine writers hovering around. No newspaper columnists are harvesting their succulent crop. You’d think it said “Contagious” on the door instead of “Quiet, Please! Shooting!”

The difference is that this is just another little picture. A B picture, if you please. B standing for Bread and Butter, or Buttons, or Bottom Budget. And standing for nearly anything else anyone wants to throw at it. But it’s a robust little mongrel and doesn’t mind the slurs, because it was weaned on them. If the trade papers give a B the nod at all, they usually sum up their comments by saying it will be good for Duals and Nabes, which is why you'll find them on a double bill in the neighborhood theaters.

A B picture isn’t a big picture that just didn’t grow up; it’s exactly what it started out to be. It’s the twenty-two-dollar suit of the clothing business, it’s the hamburger of the butcher shops, it’s a seat in the bleachers. And there’s a big market for all of them.

Only by perpetual corner cutting can these often quite presentable cheaper pictures be made to show the profit that is so very agreeable to the studios which invested their money in them.

Like the less expensive suit of clothes, the cloth from which they are fabricated is not all wool, the buttonholes are machine made, and the buttons themselves are more or less synthetic. But when you are all through, you have a suit or a picture which goes right out into the market with its big brothers and gives pretty good service at that. The trick is to judge them in their class and not by A standards.

In the finer pictures, results are all that are aimed at, let the costs fall where they may. The best possible actors are hired to articulate the finest lines the top writers can conjure up. And the best directors mount the stories in convincing and appropriate settings. Of course, occasionally somebody’s aim is a little off, but that’s beside the point.

In making a program picture, all this is different. Cheaper raw materials are used and a more thrifty approach is indicated. No expensive best seller or Broadway play is bought. That’s out; it’s not even thought about. The whole picture will be made for much less than the cost of such a property. The story used will be an original submitted by one of the freelance writers who knows just what and whom he is slanting it for. Or it may be a magazine story from one of the pulps or a fifteen-minute radio program purchased for its basic idea or twist. These properties are then blown up into script form and length by a writer who either works at the studio already or is brought in for the job. If he gets six weeks’ work out of it, he’s lucky. If he takes much more, he had better buy bonds with the money, be- cause he won’t be back very soon.

There are all kinds of ways of writing a story besides good and poor. It can be written up or written down. It can be costly to produce or slanted on the frugal side. If the cast of characters can’t be held down in numbers, it’s the wrong story for limited money. And if they can’t be kept out of busy places like night clubs, railroad depots and football games, look out for the budget.

%20(Litvak)_da%20Cin%C3%A9math%C3%A8que%20royale%20de%20Belgique%20-%20CINEMATEK.jpg)