Abbas Kiarostami’s first mid-length film, The Experience, tells the story of a photography shop errand boy who falls in love with the daughter of a client. Written by his friend Amir Naderi, a renowned director in his own right, as an autobiographical reflection, the film showcases Kiarostami's minimalist and distanced style in full form and stands out as one of his significant works exploring desire and rejection.

Wednesday, 16 October 2024

The Stranger and the Fog (Bahram Beyzaie, 1974)

.jpg) |

| Bahram Beyzaie on the set of The Stranger and the Fog |

Impossible to see for decades, Bahram Beyzaie's dazzling The Stranger and the Fog, about a mysterious stranger arriving in a drifting boat to a coastal village and falling for a woman, is an endlessly symbolic tale in which ghosts of the past, narrow-minded villagers and forces beyond the controls of the characters take the viewer into a dizzying labyrinth of rituals. In the film's meticulously structured circular narrative, characters, times and spaces rhyme and mirror each other, turning filmmaking into an act of dreaming. Characters are the product of each other's imagination before turning into myth. The film gives the centre of both attention/desire and control to a woman of will therefore it goes beyond the confines of the victimised women of the 1970s Iranian cinema.

The Crown Jewels of Iran (Ebrahim Golestan, 1965) | MoMA

Ebrahim Golestan’s most visually dazzling documentary, The Crown Jewels of Iran is ostensibly a showcase of the precious jewels housed in the treasury of the Central Bank of Iran, but in reality, it is a bold critique of the treachery of Persian kings. The film’s narration sharply contrasts with its imagery: vibrant shots of jewels in rotation are juxtaposed with Golestan’s voice, condemning the decadence of past rulers. Banned and never shown, the film's powerful message remained hidden for years.

Chess of the Wind (Mohammad Reza Aslani, 1976)

In a mesmerizing take on House of Usher-like themes, set in a decaying feudal mansion, the death of a noble family’s matriarch sets off a power struggle. Mohammad Reza Aslani’s debut feature plunges into a labyrinth of corruption and decay within the household, subtly foreshadowing the revolution to come, while masterfully depicting the hidden inner struggles of Iranian society. This recently rediscovered gem was thought lost after its misunderstood premiere at the 1976 Tehran International Film Festival. However, in 2020, it was restored by the World Cinema Foundation and has since become one of the most acclaimed Iranian pre-revolutionary films. The film features a hauntingly eerie score by Sheyda Gharachedaghi, one of the most prolific female film composers of the 1960s and 1970s.

Brick and Mirror (Ebrahim Golestan, 1964)

|

| The cover of the original pressbook |

Iranian cinema’s first true modern masterpiece, Brick and Mirror explores fear and responsibility in the wake of the CIA- and MI6-orchestrated 1953 coup. A Dostoyevskian tale of a Tehran cab driver’s search for the mother of an abandoned baby, it presents a harrowing image of a society rife with corrupted morals and widespread alienation. While rooted in a specific social context, its message resonates universally. The characters often speak without truly communicating, their soliloquies echoing unheard in the endless night they inhabit.

Tuesday, 3 September 2024

Bonbast [Dead End] (Parviz Sayyad, 1977)

|

| Mary Apick in Bonbast |

A daydreamer of a girl (Mary Apick) sees a man standing under her window day and night. Thinking that he must be in love with her, she gets into an imaginary conversation with the man (in a fine use of inner voice) as he continues to follow her everywhere. Eventually, they talk but his and her intentions are not the same, leading to one of the most shattering endings in Iranian cinema.

In the opening title card, Sayyad mentions Anton Chekov as the inspiration for the story (the story, unmentioned, is From the Diary of a Young Girl) but adds more ambiguity by stating that "the current climate in society" prompted him to tell the story hence aiming for one of the most forward films of the late 1970s about the search for and failure in finding happiness in a society built on fear and surveillance.

Wednesday, 24 July 2024

La Ballade d'un fataliste

|

| Hugo Fregonese |

Hugo Fregonese : la Ballade d'un fataliste

Hugo Fregonese est l'une des figures les plus insaisissables de l'histoire du cinéma. Ses films, ardents et singuliers, brassent fatalité, mythes et violence crue, dans les canons esthétiques de la série B. Cette version enrichie de la rétrospective présentée à Bologne lors de la dernière édition d’Il Cinema Ritrovato rassemble des films réalisés dans cinq pays différents, dont des joyaux en version restaurée (L’Affaire de Buenos-Aires, Quand les tambours s’arrêteront) ou en copies 35 mm flambant neuves (Mardi ça saignera). Il est temps de faire entrer Fregonese, cinéaste errant et secret, dans la cours des grands.

Entouré de condamnés à mort comme lui, un prisonnier noir fredonne une chanson tout en battant la mesure : Black Tuesday. Les autres détenus, tels des lions en cages, font les cent pas au rythme de la musique. Un travelling passe de cellule en cellule, les barreaux dessinent des ombres dansantes sur les visages fiévreux. « Ferme-là, t’entends ? » s’exclame bientôt un prisonnier glacé par ce chant funèbre. Alors que son cri résonne dans les couloirs déserts de la prison, le titre du film emplit l’écran dans un grondement glaçant de musique symphonique. Ainsi commence Mardi ça saignera (1954), chef-d'œuvre resté invisible des décennies durant. C'est aussi l’instant où Hugo Fregonese, fataliste de génie, entre en scène.

Dans l’adaptation par Fregonese de l’histoire de Jack l'Éventreur, L'Étrange Mr. Slade (1953), le tueur de l’est londonien professe qu’« en vérité, il n'y a pas de criminels, il n'y a que des gens qui font ce qu'ils font parce qu'ils sont ce qu'ils sont. » Et ainsi faisait Fregonese parce que c’est ce qu’il était : un metteur en scène frénétique, toujours en cavale. L’Argentin (1908-1987) changeait de pays aussi facilement que certains passaient de studio en studio. Incarnation du cinéaste vagabond, Fregonese n’aura eu de cesse d’aller et venir, enchaînant les films de fuite ou d’évasion. Un déracinement, une inquiétude que l’on retrouve chez ses héros – individus solitaires, sur la route par choix ou parce que le destin les a condamnés à l’exil.

Né dans une famille d’immigrés Italiens, Fregonese fut l’artisan d’un cinéma de genre vif et implacable, en particulier western et polar. Sa carrière, injustement sous-estimée, pour ne pas dire totalement occultée embrasse quatre décennies et de nombreux pays : de l’Argentine son pays natal à l’Espagne, l’Italie, le Royaume-Uni ou encore l’Allemagne de l’Ouest.

Mais son nom est le plus souvent associé à son séjour hollywoodien et aux dix films qu'il y réalisa dans les années 1950 – parmi lesquels Le Raid, évocation brutale en Technicolor de la guerre de Sécession et Mardi ça saignera, « l’Edward G. Robinson le plus impitoyable de tous les temps », tous deux tournés en 1954.

L’artiste, solitaire et taciturne, ne s’épanouira jamais totalement à Hollywood. Il sillonnera ensuite l’Europe où, à l’inverse d’autres cinéastes errants comme Edgar G. Ulmer il se maintiendra à flot, obtenant même plusieurs succès dans les années 1960, dont son western allemand Les Cavaliers rouges (1964), un triomphe dans plusieurs pays européens ainsi qu'en Union Soviétique.

Le Blues du bourreau

Le monde, dans les films de Fregonese, ne tient souvent qu'à un fil — et la vie de ses héros à un nœud coulant. Jouant sur la menace de l’invisible et de la fatalité qui plane, son œuvre est construite comme un crescendo de tension dont le point d’orgue constitue un finale d’une violence physique inouïe, à l’image de la dernière scène de Quand les tambours s’arrêteront (1951), récemment restauré avec le soutien de la Film Foundation de Martin Scorsese. Pourtant, chez Fregonese, la violence est le plus souvent psychologique, hormis dans quelques-uns de ses films, plus lyriques ou spirituels, comme Le Vagabond et les Lutins (1950).

Le vacillement du monde selon Fregonese se joue aussi dans son utilisation toute personnelle des conventions. Il arrive que récit, atmosphère et perspective volent en éclat au cours du film. L’Affaire de Buenos-Aires (1949) passe brusquement du film noir au thriller d’évasion, quand Le souffle sauvage (1953), autre grand film hybride, commencé comme un néo-western, se termine en pseudo-noir. Fregonese entrelace dans son langage cinématographique fragments de vie et situations dramatiques a priori sans rapport les uns avec les autres, avec pour seul ciment une ironie douce-amère et une fascination morbide pour la débâcle et la chute de ses héros. Leur mort aussi : « quelles que soient les larmes que l’on puisse verser, le rendez-vous sera honoré » annonce sans ambage le carton d’ouverture de L’Impasse maudite. Flotte dans l’air un constant sentiment de malheur à venir, comme une ballade aux accents fatalistes.

Dans l’architecture de Fregonese, tout évoque l’enfermement : les angles de vue et l’utilisation des diagonales contribuent à tisser une toile où s’enferrent ses personnages, même lorsqu’ils sont en mouvement. Ainsi dans Les Sept Tonnerres (1957), la ville entière semble se transformer en prison.

C’est dans les espaces clos que le maître de la claustrophobie est dans son élément : décors de prison et de planques sont le théâtre d’un destin implacable. Sa maîtrise des espaces devient alors une métaphore de la mise en scène, où chaque élément est contrôlé par le cinéaste et où la violence se reflète dans le morcellement des espaces – plans cassés, plateaux effroyablement vides où tuyaux, câbles et conduits démesurés sapent tout sentiment de confort et d’appartenance.

Il est temps de réhabiliter Fregonese et d'honorer son génie discret de la série B. Voici un manifeste en six points initialement rédigé pour le festival de Bologne comme une feuille de route utile au spectateur désireux de s’orienter et de naviguer dans les films de Fregonese :

1) Vous devez vous échapper, même si vous n'avez rien à fuir. La fuite est un mode de vie.

2) Passé et mort sont une même chose – on ne peut échapper ni à l’un ni à l’autre, et il existe une étrange intimité entre les deux.

3) L’argent et l’or sont des maladies infectieuses – incurables.

4) "S'enfoncer paisiblement vers l'infini". Ce n’est pas le vers d’un poète, mais un dialogue de Fregonese : c’est ainsi que s’expriment chez lui les tueurs en série, qui philosophent régulièrement sur leur condition.

5) La plupart des choses se produisent deux fois. La seconde fois, votre chance est passée.

6) Nous nous retrouvons souvent dans des espaces vides et clos, où se joue notre destin. Ce moment arrivé, cherchez les fenêtres.

Ehsan Khoshbakht

Saturday, 20 July 2024

Khaspush (Hamo Beiknazarian, 1928)

|

| The original poster in Russian |

A Soviet production by the Armenian director Hamo Beiknazarian, Khaspush dramatises the Tobacco Revolt of 1890 in which an influential clergyman issued fatwa and banned the use of Tabaco after a Qajar king offered tobacco concession to the United Kingdom.

Il Cinema Ritrovato 2022 – Opening Speech

|

| Screening of Vittorio De Sica's Sciuscià [Shoeshine] at Arlecchino cinema |

Among the whole range of trigger warnings that tend to appear at the beginning of films nowadays, there was one I saw recently that I found genuinely moving.

It was a warning that only Aussie viewers are likely to be familiar with, addressing as it did the Australian Aboriginal peoples. It read: "This film contains images and voices of people who are no longer alive."

I needed to catch my breath. It awakened something in me in connection with this festival. What we do very often involves looking at and listening to the images and voices of the dead. Are we breaking taboos, upsetting long-lost souls?

And that’s not to mention film restoration, which brings those sights and sounds even closer to their origins, heightening the resemblance.

Thursday, 18 July 2024

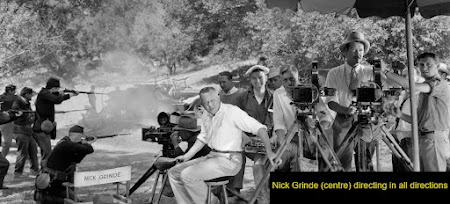

"Pictures for Peanuts" by Nick Grinde

From the Saturday Evening Post, December 29, 1945, vol. 218, no. 26

PICTURES FOR PEANUTS

By NICK GRINDE

Over on Stage 6 a million-dollar picture is starting this morning. The call was for nine little well-placed optimism you could say that the epic is beginning to show promise of getting under way. A lot of departments with a whale of a lot of mighty fine technical abilities have been working for weeks toward this very day. Propmen, grips, gaffers, electricians, boom men, recorders, mixers, cameramen, assistant cameramen, a script clerk overflowing her rose-colored slacks, a company clerk, an assistant director, his assistant and his assistant are functioning with the occupational movements that will find each one ready when the moment-finally comes to record the suspensive scene where Nancy says, ‘I am tired of wearing other people’s clothes. From now on I will wear my own or nothing!”

This confused efficiency, laced, of course, with a fine sense of self-preservation, is going on, all unnoticed, around, above and in between the associate producer and the director, who already are trying to see who can stay calm the longer. The pattern is familiar to everyone. Too much has been written about the habitat of the colossal picture for anyone to have escaped a willing or unwilling education on the subject.

But over on Stage 3 in this same studio another picture was scheduled to start this morning: at eight-thirty. It’s ten-thirty over there, too, and they have exactly two hours’ work under their belts. There are no press agents or fan-magazine writers hovering around. No newspaper columnists are harvesting their succulent crop. You’d think it said “Contagious” on the door instead of “Quiet, Please! Shooting!”

The difference is that this is just another little picture. A B picture, if you please. B standing for Bread and Butter, or Buttons, or Bottom Budget. And standing for nearly anything else anyone wants to throw at it. But it’s a robust little mongrel and doesn’t mind the slurs, because it was weaned on them. If the trade papers give a B the nod at all, they usually sum up their comments by saying it will be good for Duals and Nabes, which is why you'll find them on a double bill in the neighborhood theaters.

A B picture isn’t a big picture that just didn’t grow up; it’s exactly what it started out to be. It’s the twenty-two-dollar suit of the clothing business, it’s the hamburger of the butcher shops, it’s a seat in the bleachers. And there’s a big market for all of them.

Only by perpetual corner cutting can these often quite presentable cheaper pictures be made to show the profit that is so very agreeable to the studios which invested their money in them.

Like the less expensive suit of clothes, the cloth from which they are fabricated is not all wool, the buttonholes are machine made, and the buttons themselves are more or less synthetic. But when you are all through, you have a suit or a picture which goes right out into the market with its big brothers and gives pretty good service at that. The trick is to judge them in their class and not by A standards.

In the finer pictures, results are all that are aimed at, let the costs fall where they may. The best possible actors are hired to articulate the finest lines the top writers can conjure up. And the best directors mount the stories in convincing and appropriate settings. Of course, occasionally somebody’s aim is a little off, but that’s beside the point.

In making a program picture, all this is different. Cheaper raw materials are used and a more thrifty approach is indicated. No expensive best seller or Broadway play is bought. That’s out; it’s not even thought about. The whole picture will be made for much less than the cost of such a property. The story used will be an original submitted by one of the freelance writers who knows just what and whom he is slanting it for. Or it may be a magazine story from one of the pulps or a fifteen-minute radio program purchased for its basic idea or twist. These properties are then blown up into script form and length by a writer who either works at the studio already or is brought in for the job. If he gets six weeks’ work out of it, he’s lucky. If he takes much more, he had better buy bonds with the money, be- cause he won’t be back very soon.

There are all kinds of ways of writing a story besides good and poor. It can be written up or written down. It can be costly to produce or slanted on the frugal side. If the cast of characters can’t be held down in numbers, it’s the wrong story for limited money. And if they can’t be kept out of busy places like night clubs, railroad depots and football games, look out for the budget.