“I am very close to nature. I spend a great deal of time in the mountains. If Iran becomes a free country one day, I’d love to make wildlife documentaries,” says Mohammad Rasoulof, who fled the country last year, crossing the mountainous terrain of western Iran on foot with nothing, not even a passport (which had been confiscated). He sought refuge in Germany and added the final touches there to The Seed of the Sacred Fig, which premiered in Cannes last May. The man who could have been the David Attenborough of Iran is, until further notice, one of the foremost clandestine filmmakers from that country. “For now, the freedom and dignity of man are my top priorities,” he says. “I keep asking myself why a system allows itself to do this to us.”

Thursday, 10 July 2025

Tuesday, 23 August 2022

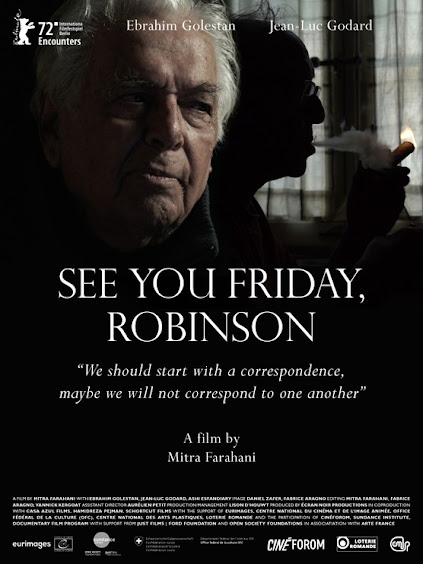

See You Friday, Robinson (Mitra Farahani, 2022)

|

RIP Ebrahim Golestan (1922 – 2023)

A long-distance dialogue between Ebrahim Golestan, a giant of Iranian cinema and literature (now only a few months shy of his 100th birthday) and Swiss-French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard forms the basis of this latest film by Mitra Farahani. Among the most gifted documentarians from Iran, Farahani mediates between two seemingly irreconcilable worlds to create a unique epistolary work. Its elegant, hybrid style takes us from encounters with shadows – the first time we see each of these artists – to the inner lives of flesh and blood individuals; vulnerable, pained, caring, endlessly searching.

Monday, 31 May 2021

Cinemadoosti: Iranian Cinephile Documentaries

|

| Poster for VHS Diaries |

A programme curated for DocuNight, currently streaming on their platform. Although I have discussed Jerry and Me here, the rights couldn't be acquired by DocuNight, so this one is not being streamed as planned. — EK

In Memory of Negahdar Jamali

This programme celebrates the intense passion for film and its possibilities that persists among Iranians, in a series of documentaries that reflect 'cinemadoosti' – the Persian word for cinephilia. These are films about daydreaming and the high price one pays for it, the story of marginalised and estranged people whose passion for cinema becomes their raison d'être.

The image of an Iranian cinephile asserts certain clichés which are not entirely unfounded: often a lonely male who collects filmic memorabilia and devours the content of film magazines; a figure occasionally facile and portentous yet burnt by an unbounded love for the movies. A name-dropper and date-of-production memoriser who likes to be seen as a walking film history, a 'cinemadoost' (cinephile) living in a parallel universe.

Thursday, 23 May 2019

50 Essential Iranian Films

|

| Kako (Shapur Gharib, 1971) |

Few years back, I asked Houshang Golmakani, the editor-in-chief of the Iranian Film Monthly, to produce a list of his 50 favourite Iranian films to be published on Keyframe. It was published around 2014 but later Keyframe went through some design and organisational changes, and the original posting, as well as some of my other contributions, vanished without any explanation. So I decided to re-post here with some minor alterations and more stills.

As I said, Golmakani edit the Film Monthly, the longest-running film magazine in Iran and one of the first to be established after the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Aside from his full-time presence in the office of Film Monthly in downtown Tehran, he has written books on Iranian cinema and directed Stardust Stricken (1996), on Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

This is not a standard listing of Iranian arthouse classics but more of a personal map of Iranian cinema -- both commercial and arthouse -- sketched for those curious people who want to explore beyond what the English film literature on Iranian cinema manages to offer, reminding the reader that Iranian cinema is not limited to names like Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf or Panahi. Aside from the work of great filmmakers with artistic ambitions since 1960s -- often dubbed as Iranian New Wave -- there are certain kinds of commercial films that deserve attention, especially those working within the confines of “national genres". This list is rather good at that. Nearly 5 years have passed since this was first compiled by Golmakani and I'm sure now his take on the subject, especially concerning recent years, would be something very different.

Fifty films essential to understanding Iranian cinema

By Houshang Golmakani(Additional notes by Ehsan Khoshbakht)

Tuesday, 13 December 2016

LFF#60: Films Consume Us, Part II

Friday, 9 September 2016

A Conversation with Tina Hassannia

Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema (The Critical Press, 2014) is the first English book about the Iranian director Asghar Farhadi, a filmmaker often overrated by most people, underrated by some.

Written by critic Tina Hassannia, the book is a dialogue of sorts in which the Iranian Canadian author, by means of Farhadi’s films, engages with her own cultural roots. The approach of the book is quite simple, yet effective: summing up the current critical reading and reception of each film in the West (and to a certain extent in Iran), supplemented by a lengthy interview with the filmmaker.

The interview below was conducted via email, a prologue to a video interview, with slightly different questions, and lots of films clips, which was done later and can be viewed on Keyframe.

Thursday, 22 October 2015

Fish & Cat (Shahram Mokri, 2013)

MAHI VA GORBEH [Fish & Cat]

Director: Shahram Mokri

Reviewed by Kiomars Vejdani

The first thing we notice about Mahi va Gorbeh is the technical challenge Shahram Mokri has taken on board. The film is shot uninterruptedly from start to finish in one long take. But film’s technical excellence is only a doorway to a dark and ambiguous world. By passing through this doorway we face a labyrinth with multitude of questions awaiting us at every corner. Within a single shot of the film we encounter numerous characters, all crammed in a limited space, their life stories cutting across each other to make a complex pattern.

Our first point of contact with the film is a crime story. Right at the beginning of the film we are informed that it is based on a true event of horrible crimes committed by owners of a restaurant in northern Iran. But despite such information, there is no visual sign of any crime within the film. It is totally free of physical violence. Mokri seems not in the least interested in crime story. His approach to film’s subject is purely philosophical. Any referral to a committed crime is indirect and nothing more than a hint like the vague cry of anguish and agony we hear from far away, or the machete Babak takes with him before going into the woods and the blood stained foul smelling bag he carries along. Any intention of crime by Babak is only implied by his way of interaction with his potential victims, either a threatening manner (like his encounter with the driver at the beginning of the film), or a cunning approach (the way he lured Parvaneh into the depth of the woods). The nearest we get to witnessing any evidence of crime is the scene of the cat holding a cut off finger in his mouth. But again instead of visually presenting such an image it is described by Mina and we only have her horrified reaction as she stares straight at us. The subjective viewpoint of camera is enough to convey her horror.

Sunday, 23 August 2015

Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema

|

| source + |

From his earliest films to the recently acclaimed The Past (which I disliked), director Asghar Farhadi has followed two existing traditions within Iranian cinema: the socially conscious realist family melodramas of the 1990s and the gritty street films of the 1970s. Though this has given his work a sense of familiarity for Iranian audiences, Farhadi has nevertheless stood out for his breathtakingly rigorous cinematic style. Outside of Iran, where these cinematic traditions are little known, Farhadi’s work appears even more audacious and captivating.

Farhadi gained widespread attention in his home country with the release of Fireworks Wednesday, but his international breakthrough came with A Separation. The latter also marked a shift in the way his audiences inside and outside Iran entered into dialogue. The Iranians, who had been generally apathetic to westerners’ regard for Abbas Kiarostami, suddenly started monitoring, through an almost systematic process of news updates and translations, all that was said and written about Farhadi abroad.

On the night of the Oscars in 2012, documented in From Iran, A Separation (Kourosh Ataee, Azadeh Moussavi, 2013), millions of eyes in Iran were locked on TVs connected to illegal satellites, broadcasting the ceremony live, as if they were watching a national sporting match. Farhadi, as if aware of his sudden stature, turned the occasion into an opportunity for international conciliation in his acceptance speech. Since the live broadcast of the presidential election debates in Iran in 2009, this was the first collective viewing experience for the nation, a ceremony which was perceived as a dialogue between Iran and the US.

Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema (The Critical Press, 2014) is the first English book about the filmmaker, written by critic Tina Hassannia whom I interviewed recently for Fandor.

Sunday, 30 November 2014

Days and Nights of Hunchback (June Festivals), Part IV

Saturday, 29 November 2014

Days and Nights of Hunchback (June Festivals), Part III

|

| از راست: حميد نفيسي، كريس فوجيوارا، ابراهيم گلستان، مانيا اكبري |

|

| ابراهيم گلستان - عكس از احسان خوشبخت |

Thursday, 27 November 2014

Days and Nights of Hunchback (June Festivals), Part II

Wednesday, 26 November 2014

Days and Nights of Hunchback (June Festivals), Part I

Tuesday, 28 October 2014

Iranian Filmmakers at LFF (English edition)

Iranian Filmmakers at LFF: Bridge Over Troubled Border

The BFI London Film Festival is practically the last stop for Iranian films on their annual festival journey, which usually kicks off at Berlinale. This year, thanks to major retrospectives of contemporary and pre-revolutionary Iranian films at Fribourg International Film Festival and the Edinburgh International Film Festival, there has been a joyous feeling of revival in the air, unprecedented since the critical success of Iranian films in the early 1990s.

Even if the retrospectives led to a belated appreciation in Europe of the Iranian New (Wave) cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, there remains much confusion about contemporary Iranian films, and this is reflected in other festival programmes. The BFI London Film Festival – known for offering an up-to-date survey of national cinemas – has shown less interest in Iranian cinema over the last few years, evident this year in the drastically low number of Iranian films being screened. This might be explained in part by two major external factors: 1) After Edinburgh’s special focus on Iran, where many of the better Iranian films of the year were handpicked by the festival, none of the same films had any chance of reaching London. LFF won’t show films premiered at EIFF. 2) The distribution of Iranian films outside of Iran has been disastrous, due to limitations in accessing the international market, the problem of cash transfer, restricted postal services and slow internet services, which rule out any possibility of uploading online screeners.

.JPG)