|

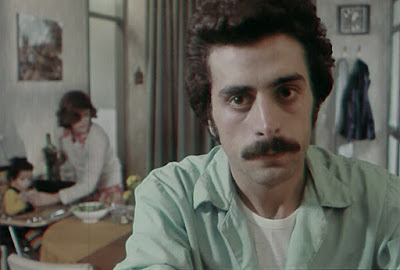

| Abbas Kiarostami circa late 60s, probably in his studio. On the wall (left) the poster for Masoud Kimiai's Come Stranger (1968), designed by Kiarostami. |

Written for Harvard Film Archive's forthcoming retrospective dedicated to Kiarostami. More info here. — EK

Known for single-handedly putting Iran on the map of international cinema, Abbas Kiarostami’s filmmaking style was shaped by a variety of Persian arts, especially poetry. Reframing the world and the relationships between individuals through his creative involvement with actors—often amateurs, often children—and showing a keen eye for the beauty of landscapes, he produced philosophical works that reinvigorated the genres of documentary and narrative fiction.

Born in 1940, Kiarostami developed a love of painting at a young age, which led him to enroll in Tehran’s University of Fine Arts. During the 1960s he was involved in the film and television industry, both as a director of commercials and as a title designer for films. After the initiation of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (known as Kanoon), which as part of its artistic activities provided funding and facilities for the production of films for or about children, Kiarostami joined the organization and made The Bread and Alley, a short film about a boy’s fear of a stray dog.